This is the final part of my essay Rehabilitating Machiavelli. Find Part I here, which deals primarily with the internal workings of a functional republic.

Book Two: Expansion & Growth

Book Two begins with some excellent introspection before turning its gaze outward and looking at ways to actually grow a republic:

Men always praise ancient times and condemn the present, but not always with good reason, and they are such partisans of the past that they celebrate not only those eras they have come to know through the records historians left behind but also those that they, having grown old, remember having seen in their younger days.

This is no less true today.

When their opinion is mistaken, as it is most of the time, I am persuaded that there are several reasons leading them to make this error. The first is that we do not know the complete truth about ancient affairs, and that most frequently those matters that would bring disgrace on those times are hidden, while other matters that would bestow them with glory are recounted most fully and magnificently.

…

I do not know, therefore, whether I deserve to be considered among those who deceive themselves if, in these discourse of mine, I praise too lavishly the times of the ancient Romans and condemn our own. Certainly, if the exceptional ability that prevailed then and the vice that prevails today were not clearer than the sun, I would speak more cautiously for fear of falling into the same deception for which I criticize others.

Given that Machiavelli spends the entire book infatuated with the ancient Romans, this self-reflection shows a good deal of maturity & wisdom. A lot of people today who yearn for the glory days could stand to read it.

Anyway, on to building things! —

The Culture War Battlefield Has Barely Moved In 500 Years [Morale]

Chapter 2: What Kinds of Peoples the Romans Had to Fight and How Stubbornly These Peoples Defended Their Liberty

Despite the chapter title, the section of this chapter I want to quote highlights that many of today’s Culture War battlefields are fought over the exact same issues as the Culture War of 500 years ago.

This segment could be ripped fresh today from any number of voices on the self-described “dissident right”:

It is not the private good but the common good that makes cities great.

In considering why all the peoples of ancient times were greater lovers of liberty than those of our own day, I believe this arises from the same cause that today makes men less strong, which I believe lies in the difference between our education and that of antiquity, based upon the difference between our religion and that of antiquity.

Ancient religion beatified only men fully possessed of worldly glory, such as the leaders of armies and the rulers of republics. Our religion has more often glorified humble and contemplative men rather than active ones. Moreover, our religion has defined the supreme good as humility, abjection, and contempt of worldly things; ancient religion located it in greatness of mind, strength of body, and in all the other things apt to make men the strongest. And if our religion requires that you have inner strength, it wants you to have the capacity to endure suffering more than to undertake brave deeds.

This way of living seems to have made the world weak and to have given it over to be plundered by wicked men, who are easily able to dominate it, since in order to go to paradise, most men think more about enduring their pains than about avenging them.

Not all my readers will be familiar with the modern 2020s version of this — an anonymous twitter profile picture, veneration of the ancient world, bodybuilding aesthetics, a disdain for modernity’s focus on humility & suffering, and animosity towards centralized finance — but Machiavelli would probably fit right in. At least until they started reading the very next chapter’s title: Chapter 3: Rome Became a Great City by Destroying the Surrounding Cities and by Freely Receiving Foreigners into Its Ranks

“Umm, is that based?”

On the surface, I do find a lot of Machiavelli’s points complaining about the decline of “modern” culture in this chapter compelling. But it’s worth holding those points up against the subsequent 500 years. Whatever the reason may be, “our religion” today has clearly dominated the competition. Perhaps Machiavelli and others may be unhappy with the final results, but they’ll need to find a compelling Molochian explanation for the sustained memetic victory of what they deem an inferior religion.

I am perhaps unqualified to write on the culturo-spiritual resonance of the Christian ethos’ commitment to suffering in public, but its rapid overthrow of the Roman religion and rise to global dominance seems impressive enough that it shouldn’t be dismissed out of hand.

At this point, 500 years on, its continued success can hardly be seen as coincidental — I might suggest that a message of “enduring their pains” resonates more among a democratic polity, whereas “avenging them” is reserved for those with the rare power to enact vengeance. A Christian ethos is therefore mutually reinforcing with the democratic arm of liberalism/republicanism/democracy, whereas the ancient Roman polytheism has a symbiotic relationship with the aristocratic arm.

And as Machiavelli notes in the next few chapters, the real power is always rooted in the people.

Pursue What Is Right, Vigorously [Methods]

Chapter 6: How the Romans Proceeded in Waging War

It is necessary both in acquiring territory and in maintaining it to try not to spend, but rather to undertake everything in a way that benefits the public treasury.

Wise words, applicable in many domains. If your bank balance is decreasing, you won’t be in charge of your own fate for long.

The Roman style and method was first of all to make wars short and massive, because by fielding enormous armies, the Romans brought to a very swift conclusion all the wars that they waged…If we take not of all those wars, we shall see that all of them were expedited, some in six days, others in ten, and still others in twenty days.

This was their custom: as soon as war was declared, they marched forth against the enemy with their armies and immediately waged a decisive battle.

There are a lot of little stories in this book where the nugget of ancient Roman wisdom essentially boils down to: pursue what is right, vigorously.

“Do the right thing, aggressively”

War, being bad and expensive, should be resolved promptly. The best way to resolve it promptly is to bring overwhelming force on short notice against ones competition. So that’s what we do.

In contrast, I think you can justifiably point to modern examples where various factions have taken an opposite approach: drawn out conflicts over multiple decades with half-hearted faux-commitments, while wracking up multi-trillion-dollar bills and ultimately failing to achieve a strategic objective. There’s more than one example.

I wrote a few years ago about what happens in the unfortunate event Rome’s massive army is defeated:

…forcibly conscript every surviving male, peasants, even slaves, make saying the word “peace” a crime, set a legal limit of 30 days on mourning, ban women from crying publicly, create a permanent standing army and not this weak-ass citizen-militia crap, and make a permanent example out of [the enemy]…

Just do it again but harder.

Why Fundraising Is Not Sufficient To Make A Great Company [Money]

Chapter 9: Wealth Is Not, Contrary to Popular Opinion, the Sinew of Warfare

…a prince must take the measure of his forces before he undertakes an enterprise and govern himself accordingly. But he must possess enough prudence not to deceive himself about his strength; and he will always deceive himself when he measures it either by money, by location, or by the goodwill of men…

I love this chapter, and it analogizes well beyond the military sphere. If you measure your startup’s worth by its fundraising, geographic location, or “the goodwill of men”…you are measuring fuzzy proxies of actual success criteria.

All these things certainly increase your power, but they do not give it to you, and by themselves they are worth nothing and serve no good purpose without faithful troops.

People who make things happen are what matters.

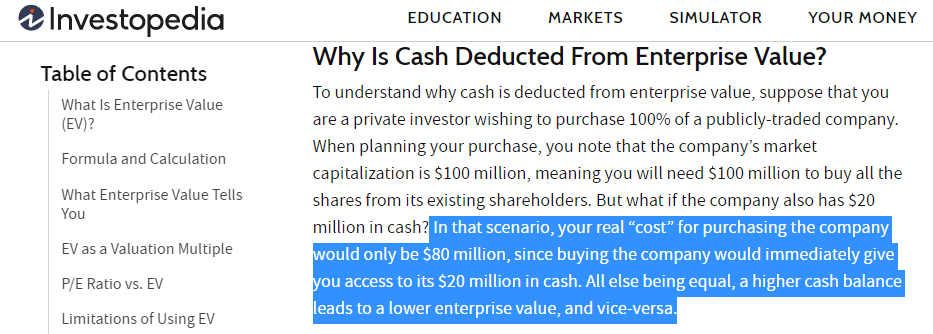

Money, moreover, not only will not defend you but will cause you to be plundered all the sooner.

When valuing a company, you subtract the value of the cash on its balance sheet from the market cap.

Much criticism is (rightly) leveled at the large American corporations who inadequately plan for market downturns and return cash directly to investors through share buybacks (see Part I) or dividends. But these corporations are often behaving rationally. Keeping cash on your books makes you a takeover target by anyone who can raise enough capital or debt to cover some of the cost — your own cash balance will cover the rest.

Money is certainly necessary as a secondary consideration, but it is a need that good soldiers overcome by themselves, because it is impossible for good soldiers to lack money, just as it is impossible for wealth alone to create good soldiers.

Obviously I’m not suggesting good-but-low-earning employees arm themselves and literally plunder established-but-complacent companies. The money is all electronic anyway, there wouldn’t be anything in the vault for you to take.

But, metaphorically, this is exactly how the startup ecosystem functions. As I noted in Ouroboros Theory: name any great startup and we can all tell you the company or industry that they metaphorically murdered on their path to greatness.

Good soldiers will not lack for money.

Money often lacks for good soldiers.

Don’t Make Deals With People Who Can’t Help You [Bad Partnerships]

Chapter 11: It Is Not a Prudent Policy to Form a Relationship With a Prince Who Has More Prestige Than Power

It should be noted that alliances concluded with princes who possess neither the ability to assist you because of their distance from you, nor the power to do so on account of their poor organization, or for some other cause, offer more fame than real assistance to those who entrust themselves to them…

The examples in this chapter are damning, but in keeping with the corporate theme I am reminded here of the general shape of a failed business partnership: a small company establishes a brand for itself but finds it lacks the resources to go after massive distribution. It then forms a partnership with a large brand with global resources. The big company gets a “hip” boost from the association, but is too sclerotic to help the smaller company do much of anything.

The end result is the diminishing of the small company’s brand, no discernible impact on the big company, and, in the worst case, the theft of any of the better performing employees or assets from the smaller company.

There’s a fun video from Donut Media about how Ford tends to do this:

Speed Over Accuracy [Decision making]

Chapter 15: Weak States Are Always Ambiguous in Their Decisions and Slow Decisions Are Always Harmful

The title does most of the work here, but:

…in the midst of doubt and uncertainty, it is impossible to match words with deeds, but once a decision has been taken and what is to be done has been determined, it is easy find the right words.

In doubtful cases and where courage is required for making decisions, such ambiguity will exist when it is weak men who deliberate and make such decisions. Nor are slow and tardy decisions any less harmful than the ambiguous ones, especially those which must be decided in favour of some ally, since slowness helps no one and is harmful to oneself.

Decisions of this kind derive either from weakness of mind or weakness in your forces, or from some malignant disposition on the part of those who have to deliberate…

Again, Machiavelli accurately describes the failure mode of institutions that have diffused decision making responsibility too much.

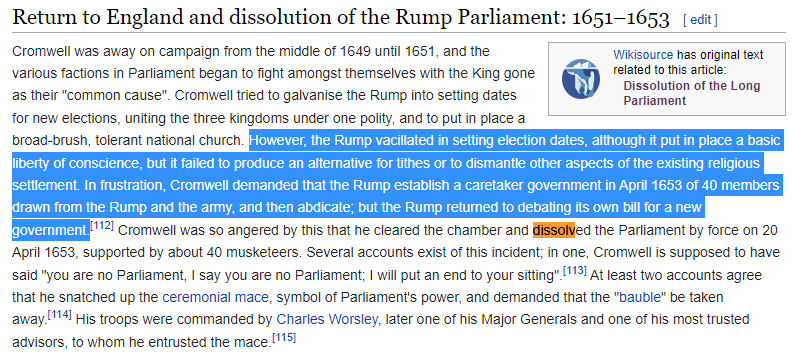

Again, 200 years later, the lessons must be learned anew:

What’s striking to me is that, again and again, Machiavelli harps on the character of the people as paramount for a republican government (he lists weakness of mind and lack of courage above), as well as civic corruption…

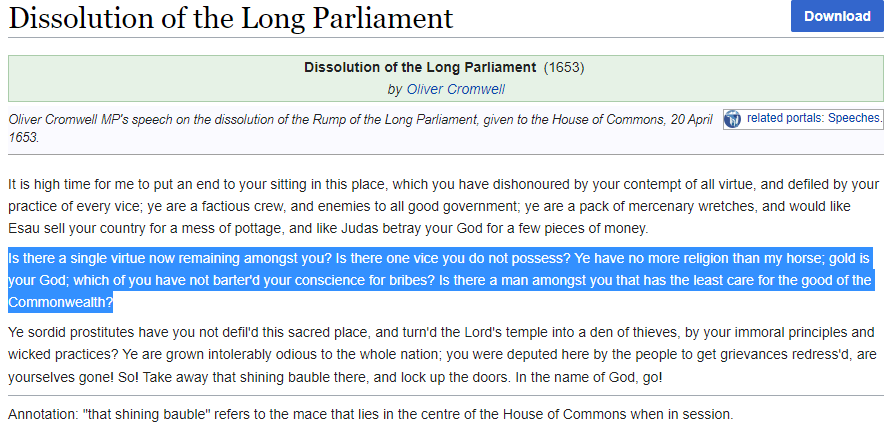

…and then you can read Cromwell’s speech to his own Parliament while dissolving it:

Now perhaps you disagree with Cromwell. Perhaps you think him a tyrannical imperialistic regicide, a left-leaning-figure who overthrew a monarchy for the people but could not abide his own principles and was corrupted by power. Perhaps you think his parliament was acting reasonably and responsibly by failing to decide a single thing for a war-torn nation attempting to exit a civil war, choosing instead to deliberate amongst themselves.

I’m not interested in arguing any of those specifics, more in seeing the ways that history rhymes with itself — and trying to observe the ways that it does not.

The Roman senate was founded 1,968 years before the English Parliament, and yet here we are again, struggling with decision making speed and suggesting horses are more fit to be in the halls of government.

Caligula smiles.

Good citizens, even when they see popular sentiment turning toward a pernicious choice, never impede the deliberations, especially in matters where there is little time.

Machiavelli quite sincerely advocates moving forward quickly in a bad direction instead of delaying things in no man’s land. An institution that is able to move fast, and accustomed to doing so, can proactively course correct if a decision turns out to be a poor one. An institution that learns the habit of delaying decisions will not.

Wartime CEOs vs. Peacetime CEOs [Executive character]

Chapter 22: How Often the Opinions of Men Are Mistaken in Their Judgments About Important Matters

How false the opinions of men are on many occasions has been seen and still is seen by those who witness their decisions; often when such decisions are not made by excellent men, they are contrary to every truth.

Because excellent men in corrupt republics (especially in tranquil times) are considered enemies, both out of envy or other ambitions, the people follow either a man who is judged to be good by common self-deception or someone put forward by men who are more likely to desire special favours than the common good.

Later, in adverse times, this deception is revealed, and out of necessity the people turn to those who in tranquil times were almost forgotten.

Certain situations also arise in which men who have little experience of things are easily deceived, since in such incidents there is much that seems so true that it makes men believe their judgments in these matters are accurate.

“People are often wrong” shouldn’t be news to anyone — but the specific mechanisms described here are timeless. How to ensure that “excellent men” are valued and those with “little experience” are not deceived is a continual problem for institutions that depend on mass opinion.

Seeing who people turn to in a crisis is always revealing, whether Ulysses S. Grant or Steve Jobs.

I think this chapter also provides an interesting alternative lens through which to appreciate Ben Horowitz’s “wartime CEO vs. peacetime CEO” point — to some extent the lessons he mentions taught in management programs for “peacetime management” could be viewed as techniques to manage, mitigate, or manipulate the judgment of internal stakeholders as opposed to achieving external outcomes. In this framing, the role of a “Peacetime CEO” is simply to prevent civil war breaking out and/or the dethroning of himself or other executives — as opposed to a “Wartime CEO”, whose role is to achieve something.

Shame & Society [Making Enemies]

Chapter 23: To What Extent the Romans Avoided a Middle Course of Action in Passing Judgements on Subjects for Some Incident Requiring Such a Verdict

When one has to judge powerful cities and cities that are accustomed to living in liberty, it is necessary either to destroy them or to give them benefits; otherwise every judgement is made in vain.

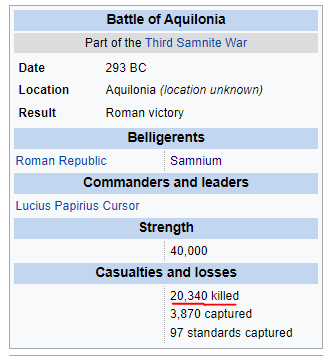

Above all one must avoid a middle course of action, which is harmful, as it was to the Samnites when they trapped the Romans at the Caudine Forks and did not wish to accept the opinion of the old man who advised them that all the Romans should either be released with honour or killed, but, choosing a middle course of action, they disarmed the Romans and forced them to march under the yoke, allowing them to depart full of shame and indignation.

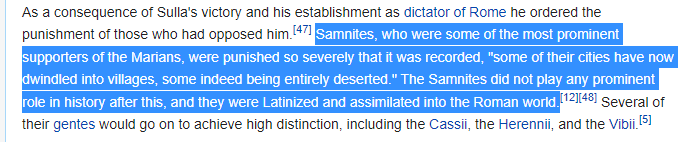

I wonder how this turned out for the Samnites?

This story is what happens when Ender’s rule from Part I is not followed — “win all the next ones too.”

As a result, not long afterwards they learned, at great cost to themselves, that the old man’s judgement had been useful and their own decision harmful.

And then later…

The discussion of this chapter touches on how the right decision, hard and unpleasant though it may be, can be overruled by “ignorant or cowardly” men:

…those who seemed to be wiser declared that killing the Romans would bring little honour upon the city…

This is certainly true…

Men who hold such opinions fail to see that men taken individually, and a city as a whole, sometimes sin against the state in such a way that in order to make an example to others for one’s own security, a ruler has no other remedy than to destroy them.

…but when security and magnanimity are in clear conflict, honour should not be allowed to weaken the state in a way that results in later harm to its citizens.

Honour consists in being able and knowing how to punish them, not in being able to hold them amidst a thousand dangers, because a ruler who does not punish a man who errs in such a way that he cannot err again is held to be either ignorant or cowardly.

I’m excerpting here, but to be clear: Machiavelli is not supporting harsh & permanent punishment for all crimes or opponents — simply that making enemies is really bad on an existential level, even if those enemies don’t appear to be powerful today. The “middle course of action” from this chapter’s title is the realm of men without the courage of their convictions, and while you might get away with it more often than not, enacting small punishments and indignities is an excellent way to get yourself Samnite’d.

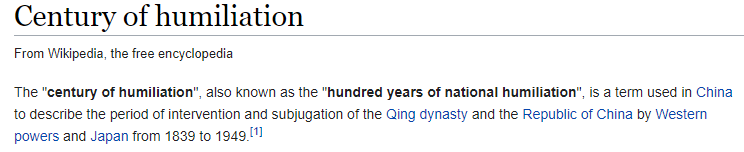

What’s refreshing to me here is the full conception of the emotional character of social relations between groups of people. Modern analyses of these things often remain in the “rational” realm and ditch an evaluation of the emotional as unmeasurable and unscientific.

But both at the individual and Great Power level, these things do matter, and they have deep security implications. The existence of wikipedia pages like this is not a sign of great wise prior actions:

And you can read this book for a detailed exploration of similar themes:

You don’t need to be TLP to understand that shame is often a prelude to rage.

Walls Are For Losers [Offense]

Chapter 24: Fortresses Are Generally Much More Harmful Than Useful

Best chapter in the whole book.

He gives three arguments for why defensive structures of any kind do more harm than good:

(i) Defense against your own citizens:

To the wise men of our times, it will perhaps seem a matter not well considered that the Romans, in their desire to secure themselves from their neighbours, did not think of building fortresses…

Indeed. Why didn’t they?

Consider whether fortresses are constructed to defend against one’s enemy or against one’s subjects. In the first case they are not necessary, in the second they are harmful.

Not necessary against one’s enemy?? Harmful against your own citizens??

Where a principality or a republic fears its subjects and the possibility of their rebellion, such a fear must arise first of all from the hatred that its subjects harbour for it, hatred for its evil conduct. This evil conduct arises from the belief that it can hold its subjects with force, or from the lack of prudence of the one who governs them.

The logic chain here is: Bad government or excessive use of force => population hates you => threat of rebellion => fear the population => use more force than you should => repeat cycle until revolution.

If you didn’t believe yourself to be “safe” from your own citizens, you wouldn’t treat them so badly in the first place:

One of the things that makes him believe he can then rule them by force is having fortresses nearby…for in the first place, they make you more bold and violent toward your subjects, and then they fail to give you the security within, since all the forces and all the violence used to hold a people are worth nothing unless you can put a good army in the field, as the Romans did, or you disperse, destroy, disorganize, and disunite the people in such a way that they cannot unite to harm you.

The second order consequence of a fortress is treating your subjects worse than you otherwise would have, believing yourself to be secure. The moral hazard here is Machiavelli’s point.

If you read this and are just taking it all literally, then it’s a neat historical story of limited relevance. We don’t build fortresses much today: artillery and MOABs break them apart, and targeted long-range offensive options mean large armies rarely congregate in one place.

But a Fortress is a perfectly good metaphor: something that took investment to build that you believe offers some form of defensive protection.

Unless you have offensive counterattack options — that require you to leave your fortress walls — no amount of defense will protect you from a determined enemy.

Pictured: regrets

(ii) Defense against conquered peoples:

In a city to which your very name is inimical, follow the Roman method: either make it your ally or destroy it.

In cities they wished to hold with force, they tore down the walls instead of building them.

The examples and counter-examples in this section are good reading, but the point stands on its own.

Having conquered a people one time, removing their defensive walls trivializes the next time (if there is a next time), while also making future rebellion less likely by reducing the psychological security conferred by defensive structures described in section (i).

(iii) Defense against invading peoples:

Fortresses are unnecessary for those peoples and kingdoms that have good armies, and for those that do not have good armies they are useless, because good armies without fortresses are sufficient, while fortresses without good armies cannot defend you.

The Spartans not only abstained from building fortresses, but also did not permit their city to have walls, because they wanted the exceptional ability of the individual man, and no other type of defence, to protect them.

Walls lead to weakness, weakness leads to being conquered — it’s a pretty contrarian take and I love it.

A prince who has good armies will sometimes find fortresses on the coasts and borders of his state useful in holding back the enemy for a few days until he has put things in order, but they are not essential.

Why waste valuable scarce resources on walls?

You have enemies?

No problem.

Either make them an ally. Or destroy them.

“Walls, you say?"

External Threats Unify Republics [Evaluating enemies]

Chapter 25: It Is a Mistaken Policy to Attack a Divided City in Order to Occupy It as a Result of Its Disunity

Japanese generals circa 1942 must have missed this chapter:

The cause of disunity in republics is in most cases idleness and peace; the cause of unity is fear and warfare.

This lens suggests perhaps that America’s current polarization might be a result of an extended period of uncontested hegemony. I’m not saying that’s true, but it might be nice if it were.

Of course there is a right way to do these things, if you really must:

The proper method is to seek to gain the confidence of the city that is disunited and, until the people come to the point of fighting, to act as their arbiter, maneuvering between the factions. When fighting breaks out, it is appropriate to give small favours to the weakest faction, so that they continue fighting for a longer time and wear themselves down, and so that larger forces never make them all suspect that you intend to overcome them and become their ruler.

The Consequences of Ideological Blind Spots [Speech]

Chapter 28: How Dangerous It Is for a Republic or a Prince Not to Avenge an Injury Committed Against the Public or Against a Private Individual

Here we learn that the end result of disrespecting foreign ambassadors is an invasion of the Roman Republic and a great deal of death and suffering.

This disaster came upon the Romans solely because of their failure to observe justice, for after their ambassadors had transgressed ‘against the law of nations’ and should have been punished, they were honored.

Nevertheless, it must be considered how much care every republic and every prince should take not to commit such an injury, not only against a mass of people but also against any single individual, because if a man is greatly offended either by the state or by a private person and is not avenged to his own satisfaction, he will never be appeased until in some way he has avenged himself upon the prince, even if he sees his own harm in it.

The discussion of the assassination of Philip of Macedon in this chapter seems like a clear cut case to me (and indeed, assassinations of politicians often follow this mold). As a political leader you become a magnet for blame for negative outcomes, even if you were not directly responsible for them yourself.

Machiavelli describes Attalus, one of Philip’s generals:

Having organized a formal banquet to which Pausanias and many other noble barons came, after each guest was full of food and drink, he had Pausanias seized and brought to him with no hope of escape, not only fulfilling his own lust by force but also, to bring him even greater dishonour, allowing many others to violate him in the same way.'

Not nice.

Pausanias complained more than once about this insult to Philip; after keeping him for some time in the hope of being avenged, Philip not only failed to avenge him but made Attalus governor of a province in Greece; hence Pausanias, seeing his enemy honored and unpunished, turned all his indignation not against the man who had done him the injury but against Philip who had not avenged him.

If you’re unfamiliar with the story, it concludes predictably with Pausanias brutally stabbing Philip to death at a public theatre.

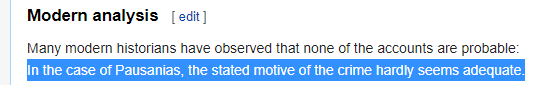

I highlight this because the Wikipedia page of this account describes the same rape, but then also adds:

Which just shocks me.

One thought occurred to me while reading: it’s not really possible to push back on this “hardly seems adequate” position without Fedposting:

If you’re just a humble online writer, or an academic, this is not such a big deal. You can simply repeat along with me: “nothing could ever justify engaging in violence against political leaders outside of the justice system”, and move on.

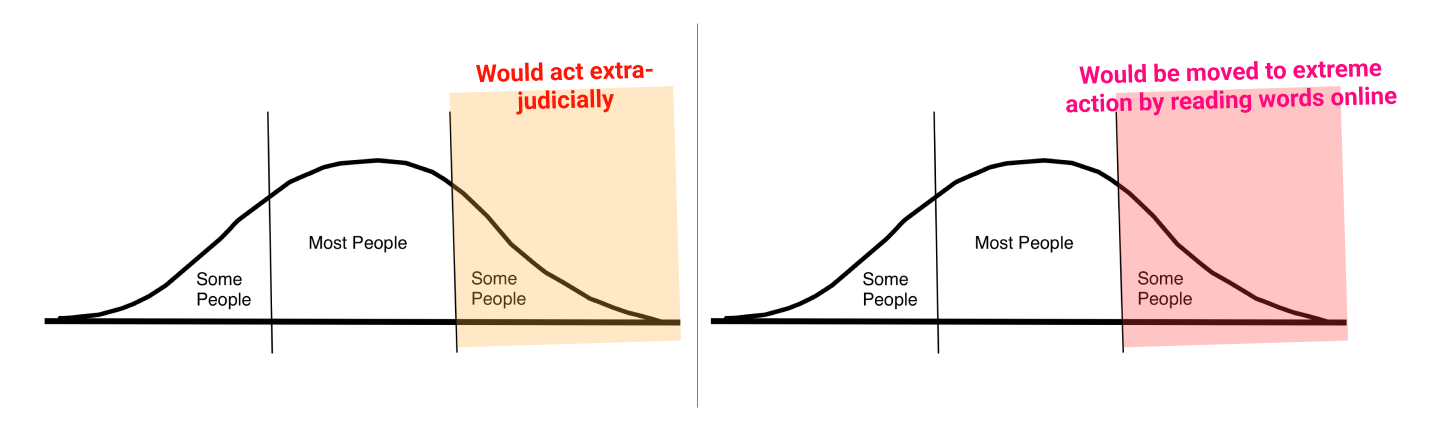

But if you’re actually involved in governing, or worse in the Justice system itself, the consequences of ignoring these lessons can ultimately be existential for your institution. I think there’s likely a spectrum here, and while the average man probably will suffer injustice and not act upon it in any way that would have negative repercussions — as with most things, it’s the extremes of the bell curve that shape dangerous outcomes.

This example is worthy of note to anyone who governs: he must never esteem a man so lightly that, piling injury upon injury, he believes that the injured man does not think about taking revenge despite all the danger and harm that might befall him.

I actually think this story and its “hardly seems adequate” Wikipedia summary is a good example of how a subtle societal norm can shape which ideas get signal boosted and which get self-suppressed. When you stack two of these social norms together, like so:

…and combine them with the knowledge of intersectional extremism that exists at the other end…

…it would be irresponsible to publish anything other than condemnations and disavowals and/or confusion at Pausanias’ actions.

And then, if you, as a civic leader, take the invisibility of those stacked orange & red sections as evidence of their non-existence, you get a real rude awakening when you go out to see a local performance.

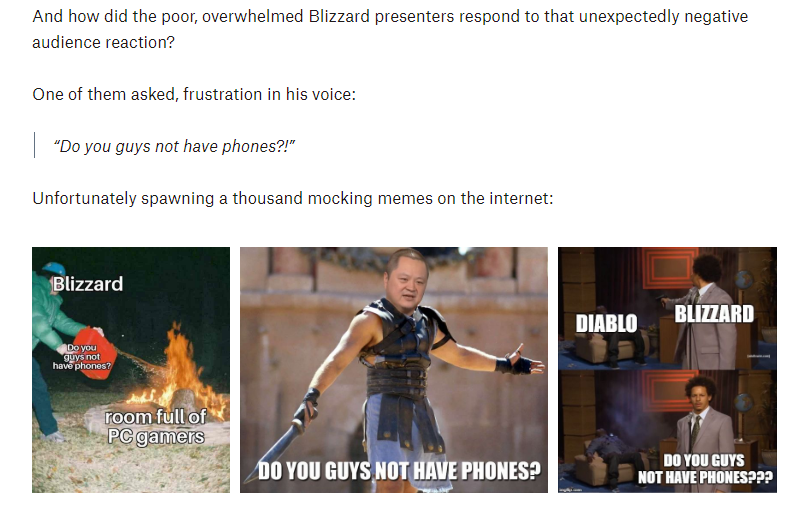

This is all dreary stuff in the realm of politics and history, but I suspect there are many occasions where a company’s internal politico-cultural framework leads to the stacking of certain norms around what is said and what is not said, that then later leads to organizational blind spots and company blunders, ala:

This is of course not to draw an equivalency here, merely an analogy for how a whole group of people might convince themselves of a truth that simply wasn’t: namely, that an audience of 35,000 hardcore PC gaming fans who forked over $1k-$3k to attend a PC gaming convention in-person would be enthusiastic about a mobile-only cash-grab game.

Don’t Trust, and Verify [Judgment]

Chapter 31: How Dangerous It Is To Believe Exiles

One must consider, therefore, how vain are both the word and promises of those who find themselves deprived of their homeland. Accordingly, with respect to their word, it must be assumed that any time they can return to their native land by any other means than with your assistance, they will abandon you and draw near to others, notwithstanding whatever promises they have made to you.

As for their vain promises and hopes, their desire to return home is so intense that they naturally believe many things which are false, and to them they add many things with guile, so that between the things they believe and the things they say they believe to fill you with hope, they fill you up with so much hope that if you rely upon it, you either incur expenses or undertake an enterprise in which you are ruined.

Harsh words, but if you recognize this photo, I need say no more.

On Micromanaging [Delegation]

Chapter 33: How the Romans Gave the Commanders of Their Armies Full Discretionary Powers

Among other matters worthy of consideration is an examination of the kind of authority with which the senate sent out their consuls, dictators, and other military commanders. It is evident that such authority was extremely great, and that the senate reserved nothing for itself except the authority to start new wars and to confirm peace treaties, while leaving everything else to the will and power of the consul.

Anyone who considers this approach well will see that it was very prudently employed, for if the senate had wished for a consul to proceed in war little by little according to what tasks they entrusted to him, they would have made him less diligent and slower…

Besides this, the senate would have been obliged to give advice on a matter about which it could not have known anything, since despite the fact that the senate was filled with men highly experienced in warfare, nevertheless, not being on the spot and not knowing the countless details that must be known in order to give good advice, they would have committed countless errors in giving it.

This is a policy I most willingly note because I see that the republics of the present day, such as the Venetian and Florentine republics, understand the question differently, and if their military leaders, quartermasters, and agents have to set up a single artillery piece, they want to know about it and give advice on it.

The military and political implications of democratic micromanagement are still incredibly relevant today.

But the business and economic implications are just as severe. You can read a thousand tweets a day about The Fed — or any Central Bank of your choice. You can read another thousand armchair CEOing the decisions of a handful of executives at companies that capture the public eye.

And that’s just the masses, who would be the Plebeians by analogy to Rome. Machiavelli’s point was about the Senate itself, and our own Congress has lately grown fond of dragging executives before it to answer to a parade of horrifically formed questions. Or you can open your favourite media publication’s homepage and see more of the same. Or tune in to your favorite business podcast.

…nevertheless, not being on the spot and not knowing the countless details that must be known in order to give good advice, they would have committed countless errors in giving it.

But beyond taking easy shots at the commentariat, the main lesson here for modernity is the appropriate delegation of power when operating in the fog of war, when timing is important, and when potential outcomes could be huge.

Namely: reserve nothing for yourself except what direction to point in.

Book Three: Ad-hoc Advice

There are many good chapters in Book 3, but they don’t lend themselves cleanly to a theme. The chapter on “Conspiracies” has been quoted by people in recent times, most scandalously in the takedown of Gawker Media, and while it’s the longest chapter in Machiavelli’s book I don’t think it’s the most insightful. Focusing on this chapter suggests the reader barely read any of the others — which is more reasonable than it sounds, given that the chapter is ~30 pages by itself, in a book whose other chapters never go beyond 5 pages.

This oddity is noteworthy, and I think a Straussian reading of the chapter is reasonable, and if you are trying to overthrow a government, or an adversary who can destroy you right up until you finalize them, you probably should give it a close read. But otherwise…there’s more valuable material elsewhere. I call this out here because you can make a case that the existence of the “Conspiracies” chapter changes how much of Book 3 should be read and I’m going to interpret it all literally instead of as an elaborate deception.

Make your own judgment.

When You Must, Tempt Fortune [Leadership]

Chapter 10: That a Commander Cannot Avoid a Battle When His Opponent Insists on Fighting Under Any Circumstances

A prince who has put together an army and sees that, for lack of money or friends, he cannot keep such an army together for long is completely mad if he does not tempt fortune before that army falls apart, because by waiting he will certainly lose, and by trying he may win.

Another thing to be considered carefully here is that even if one is going to lose, one must wish to acquire glory, and there is more glory in being defeated by a force than by some other difficulty that has caused you to lose.

Some of the best advice for Founders and executives in general in this chapter. The fog of war is real, the future uncertain, and sometimes things look dire af.

The scenario presented: you’ve assembled a great team but you can’t keep them together for too much longer, defeat is certain once the team dissolves, but victory looks unlikely in the present moment.

The advice given is not to self-immolate or make foolish decisions — the advice is to dare greatly and play the only line that has a chance of winning.

Beware Co-Captains [Leadership]

Chapter 15: That One Man and Not Many Should Be Placed in Command of an Army, and How More Than One Commander Is Harmful

Beating the same drum as before here, and again I just include this because I can’t help laughing at events from 500 years ago:

Livy declares: ‘It is most salutary that in the administration of great undertakings, the supreme command should be in the hands of a single man.’

This is exactly the opposite of what our republics and principalities do today, when, in order to administrate them better, they send into places more than one commissioner and more than one leader; this creates an immeasurable confusion. If the reasons for the ruin of the Italian and French armies in our times were to be sought, this would be the principal explanation.

It is truly possible to conclude that it is better to send one man of average prudence on an expedition alone than two extremely capable men with the same authority together.

Treat Your Reports Kindly [Leadership]

Chapter 17: That You Should Not Offend a Man and Then Appoint Him to an Important Governmental Post

Title seems like a “duh, no shit” thing, but witness:

Once this was learned in Rome, it earned Claudius Nero the condemnation of both the senate and the people, and he was criticized in an offensive way throughout the city, much to his dishonour and disdain…

Then they put him in charge of another army and sent him off again.

He decides to risk it all on a crazy & unnecessary gamble.

Later, when Claudius was asked why he had taken such a dangerous decision, in which without dire necessity he had almost gambled Roman liberty away, he replied that he had done it because he knew that if he succeeded, he would regain the glory that he had lost in Spain, and that if he failed and his decision had the opposite outcome, he would avenge himself upon the city and those citizens who had so ungratefully and shamelessly insulted him.

No shit.

It follows that it is impossible to organize an everlasting republic, because its downfall can come about in a thousand unforeseen ways.

Unforeseen or not, the title of this chapter — don’t disparage people and then give them power over you — seems like an obvious no-brainer. Executives who like to abuse or denigrate their employees ought to keep this one in mind.

Play To Win, Read Your Opponent [Tactics]

Chapter 18: Nothing Is More Worthy of a Commander Than to Anticipate the Decisions of the Enemy

I’m a huge fan of Sirlin’s Play to Win series of essays / free online book, who defines the ability to profit from anticipating the decisions of an opponent as the mark of a good competitive game:

Machiavelli concurs:

Epaminondas the Theban used to say that nothing was more necessary and more useful to a commander than having some knowledge of the deliberations and decisions of the enemy. Since such knowledge is difficult to obtain, the commander deserves even more praise when he does so by speculation.

The very best competitors can often incept certain ideas into their opponents. It’s a lot easier to know what your enemy is thinking if you can lead him by the nose to think exactly what you want.

No Factions in France? [Overcoming objections]

Chapter 27: How to Unify a Divided City, and Why the Opinion that It Is Necessary to Keep Cities Divided In Order to Hold Them Is Not True

Obviously this chapter jumps out at me because of the current political polarization and extremity of ‘faction’ that characterizes modern times.

But putting the tinfoil on hold for a moment, Machiavelli finds reuniting divided polities to be very simple:

The method of how to reunite a divided city may be noted: this method consists of nothing else, nor can the wound be healed in any other way, but executing the leaders of the disturbances.

Ah. Errr. Can we pause the Fedposting for a second please, sir?

For it is necessary to choose one of three methods: either execute them, as the Romans did; or remove them from the city; or force them to make peace among themselves under the obligation of causing no more harm.

okay let’s just go with the last one?

Of these three methods, the last is the most damaging, the least certain, and the most useless, because where much blood has been spilled or other similar injuries have been inflicted, it is impossible for a peace made by force to endure, with the parties meeting face to face every day; it is difficult for them to abstain from offending each other, with new occasions for complaints arising among them every day through their close association.

A thoroughly depressing analysis.

I hope & assume this is a good example of a time that Machiavelli was completely wrong.

Later in the same chapter, he continues:

If a republic governs it, there is no finer method of making your citizens wicked and causing divisions in your own city than to control a city that is divided, because each faction seeks to win favours and each creates friends through various corrupt means.

Two extremely great disadvantages arise from this: one, you never make the people your friends, for the reason that you cannot govern them well, since you must often vary the government, now with one humor, now with another and second, such concern with factions of necessity further divides your republic.

He then tells a story from contemporary 1500s Florentine affairs:

Monsieur de Lant harshly criticized this division, stating that if in France one of the king’s subjects declared he was in the king’s faction, he would be punished, because such a statement signified nothing other than that people who were the king’s enemies lived in that city, and the king wanted all the cities to be friendly to him, united, and without factions.

The opinion that division is necessary to rule arises from the weakness of those who are rulers. With the realization that they cannot hold states with force and with exceptional skill, they turn to such schemes, which are occasionally useful in quiet times, but when adversities and hard times arrive, they display their false nature.

Contra “executing the leaders of the disturbances”, this degree of unification does seem admirable and worth striving for. It’s hard to reconcile the division discussed in this chapter in a negative light with the “healthy conflict” discussed in Part I, but I think Machiavelli’s case would be that the “faction” described in this chapter is somehow different from the divisions between Consul/Senate/Plebeian.

Given how the “party lines” split at the time Caesar & Octavian turned the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire, I find this view unsatisfactory. The nuanced reality is likely that, on many occasions, internal political conflict is a sign of healthy politics and Live Players…right up until it isn’t.

It follows that it is impossible to organize an everlasting republic, because its downfall can come about in a thousand unforeseen ways.

Moses the Mass Murderer [Memes]

Chapter 30: That a Citizen in His Own Republic Who Wishes to Employ His Authority for Some Good Work Must First Extinguish Envy

Including for this one amazing sentence:

Anyone who reads the Bible intelligently will see that, in order to advance his laws and his institutions, Moses was forced to kill countless men, who were moved to oppose his plans by nothing more than envy.

Legendary take.

I think in Machiavelli’s worldview, this is actually an excellent move and he’s praising Moses here for his realpolitik, which just makes it even funnier.

Why Advisors End Up Depressed Or Cancelled [Scope]

Chapter 35: What Risks Are Run in Making Oneself the Leader by Counseling an undertaking; and How Much Greater the Risks Are When the Undertaking Is an Extraordinary One

Since men judge things by their results, all the evil that comes about is blamed upon the one who gave the advice, and if things turn out well, he is commended for it; but the reward is far from counterbalancing the blame.

Founders and advisers and execs take note.

It is therefore quite certain that those who give advice to a republic find themselves amidst these difficulties: that is, if they do not recommend without reservation the policies they believe to be useful, they fail in their duties; and if they give such advice, they place their lives and their position at risk, because all men are blind in the sense that they judge good and bad advice by the results.

After considering how to avoid either this infamy or this danger, I see no other path to follow than that of choosing moderate undertakings and never seizing upon any of them as your own, and that of speaking your mind without passion and, without passion, defending it with modesty.

A chapter filled with regret, the words obviously echo Machiavelli’s own personal career trajectory (aka exile and forced retirement and a three week stint being “…hanged from his bound wrists from the back, forcing the arms to bear the body’s weight and dislocating the shoulders…”)

What’s sad here is that his ultimate conclusion — choose moderate undertakings, do not seize upon them as your own — is aligned with a “corrupt” society, per his own definition from Part I. The “Roman way” Machiavelli prizes so much would simply be to do what is right, vigorously, and suffer the consequences.

Of course that’s easy to say from my position of not-being-made-to-suffer-three-weeks-of-consequences.

The dividing line between “Actor” and “Advisor” is thin in many ways, but infinitely large in others.

And in this chapter Machiavelli is lamenting the fact that Actors hold Advisors responsible for their advice in the exact same way that the masses or the aristocracy would hold the Actor accountable. This asymmetry is severe and will feel unreasonable to most who serve in this role, because their upside is much more limited than the Actor’s upside.

Of course the alternative is simple: take the reins of action yourself and step out of the advisor role. You’ll keep the same downsides, but get more upside. Win-win.

I call this “the Lenin play”.

“Who advises whom”, as they say. Watch out for icepicks.

The Unfortunate Persistence of Unjust Stereotypes [Memes 2]

Chapter 36: The Reasons Why the French Have Been and Are Still Considered More Than Men at the Outset of a Battle and, Later on, Less Than Women

Including this because the title took me by surprise, given that such unfair stereotypes are still repeated today in America.

Even more: Machiavelli’s specific diagnosis in this chapter is that the French have an incredible amount of “passion,” but only a limited amount of “order.”

While I would of course not condone any stereotyping whatsoever, on any occasion, I do find this hilarious given that it was written 500 years ago. Blame it on my Anglo heritage.

In an entirely unrelated event, the title of Chapter 43 is: “Men Born in One Province Display Almost the Same Nature in Every Age”, and consists of a description of the unchanging character of cultural transmission & socialization through across eras.

You Will Not Become Great When You Get The Title, You Get The Title When You Become Great [Rank]

Chapter 38: What a Commander Should Be Like to Gain the Trust of the Army

“Not by means of political faction nor through the conspiracies beloved of the nobility have I won for myself three consulships and the highest praise, but by this right hand of mine.”

These words, carefully examined, will teach anyone how a man must conduct himself if he wishes to hold the rank of commander, and anyone who is not like this will discover in the passing of time that this rank, when it is held through fortune or through ambition, will have the effect of stripping him of any reputation, not of bestowing it upon him; because it is not titles that make men illustrious, but men who make the titles illustrious.

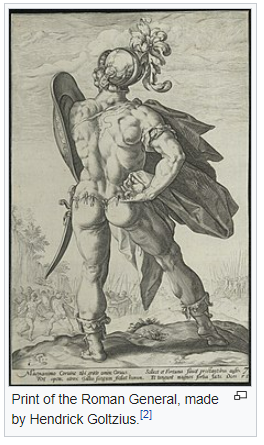

If your speech about why people should follow you isn’t inspiring artists to paint pictures like this of you 1,600 years later, are you really in charge?

Do New Things [Staying Alive]

Chapter 49: If a Republic Is to Be Kept Free, Each Day It Requires New Measures

Last chapter in the whole book here.

Its message is a fitting one.

You cannot know what is coming in the future:

Every day in a great city, accidents necessarily arise that require a physician, and the more important such accidents are, the more necessary it is to find the wisest physician.

For a Republic to survive, it needs to be a “Live Player”, able to do new things:

Many of the individual themes in this book come down to this final point. Agility, consistency, wisdom, a bias to action, and the absence of corruption, all come together to enable a Republic to overcome whatever life throws at it.

You aren’t going to be successful forever. Entropy always wins in the end. But between now and then, you can make a glorious showing of it.

Conclusion: Becoming Elden Lord

So we’re at the end of the book now, at last, and this review has ballooned in length to nearly become its own standalone book. If you consider the length of Livy’s original Ab Urbe Condita compared to Machiavelli’s own Discourses, I think I’m roughly in line with the shortening tradition. Another 2 or 3 reviews down the rabbit hole and you might have something readable in a single sitting.

But you can say one thing about Machiavelli’s review that you can’t about mine: he filled his with original or semi-original theses about the structure of a healthy government. I mostly just made observations. My only defense here is that Machiavelli published posthumously. You’ll have to sift through a 4 hour podcast if you want to hear anything more specific from me (thanks to Lorenzo and the Swarm podcast for hosting me this week, give it a listen here!)

Still, I did have one encapsulating thought that I want to leave on, and a brief story to pair it with.

I had a little extra time in the evenings recently and started playing a newly released game called Elden Ring. It’s known for being brutally punishing to new players (that’s me). After my 32nd death to a generic NPC, I went looking on Reddit for help and tips with my underperforming character build. There I saw a comment that’s a bit of a meme in the community:

aka your own terrible choices making your character are the reason the game is hard

Having read the whole book twice over now, if I had to condense Discourses on Livy down to a single meta-thesis it would be:

A republic is a reflection of its people; a tyranny of its tyrant. The problems of a republic are diffused across the people, while those of a tyranny are concentrated in the tyrant.

I like this framework, as concentrated problems are also much more visible, and solutions will appear simple and obvious — whereas diffused problems will tend to escape notice and solutions are hard as hell. Most of this book wrestles with the various pitfalls of diffused problems — responsibility, decision making, & accountability.

In a system of centralized power and authority, the primary issues are succession and the character of the autocrat.

In a republic, the primary problems are decision-making and the character of the people. To the extent the other topics are also issues, it’s as a reflection on the people themselves and not the structure of the republic — else they would simply change things.

So in as far as you have issues with the outputs of any republican institution, my response having read Discourses on Livy is:

My brothers in Christ, YOU made the government

You’ll be pleased to know my Elden Ring story has a happy ending: I took some responsibility for my misallocated experience points, put my head down and grinded for a bit, and was then able to rejigger my build into something that let me slay the harder bosses.

I wish all readers similarly happy endings :)

At the end of the day, you make the build.